"Everything not saved will be lost."

How do we navigate the use of AI while preserving existing skills and knowledge?

"Everything not saved will be lost." the old Nintendo Video Game warning read as the system shuts down. Who knew the Nintendo warning message would feel like a profound prophecy of the perils of losing knowledge and skills today?

I read recently that over 2 million research papers have vanished from the internet and that there are no physical copies. We are losing more information each day than is being produced. We tend to embrace adopting each new technological advance while presuming that established skills and knowledge take care of themselves and don't require any protection. Efficiency, convenience, and profit are the name of the game, but we need to think about how endurable that is and the value of the skills we might lose in the process.

The Renaissance was made possible by rediscovering ancient Roman buildings, sculptures, and construction methods lost for centuries in the so-called Dark Ages. We have grown to complacently believe that knowledge always increases and that each advancement in technology adds to humanity's library of understanding and skills. However, as the Dark Ages show, knowledge can be lost as well as gained, and once lost, it can be exceedingly difficult to get back.

In the 1400s, the cathedral of Florence, Santa Maria Novella, had been left open to the skies for eighty years because no one could find a way to build a dome to cover the gap. There was no method to stop the walls from collapsing inwards. Despite many failed attempts, a solution was finally found by analysing the Pantheon of Rome and examining how it was built. That knowledge was lost for centuries but eventually recovered and pieced together during the Renaissance.

Unless they are saved and preserved, knowledge and skills are lost. The tailors on Saville Row, who could cut and make a suit to the same standards as those Cary Grant wore a century ago, are probably a dying breed. I often walk into an old church building in England and marvel at the skills required to build it, and I wonder if that local building knowledge and know-how have been misplaced for good.

In the coming era of AI, there's a real risk that we will relinquish a swath of human-based skills and knowledge as we delegate more and more to AI, and a key challenge will be finding a way to preserve those skills.

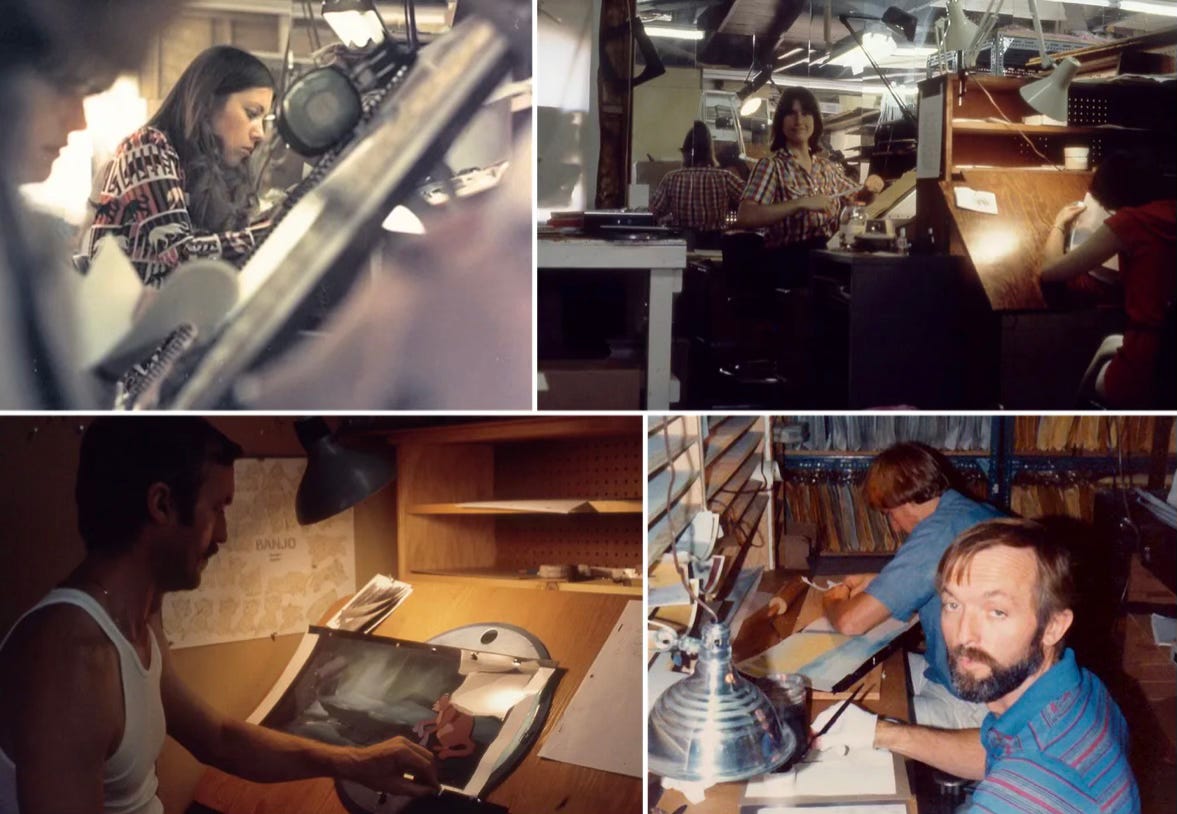

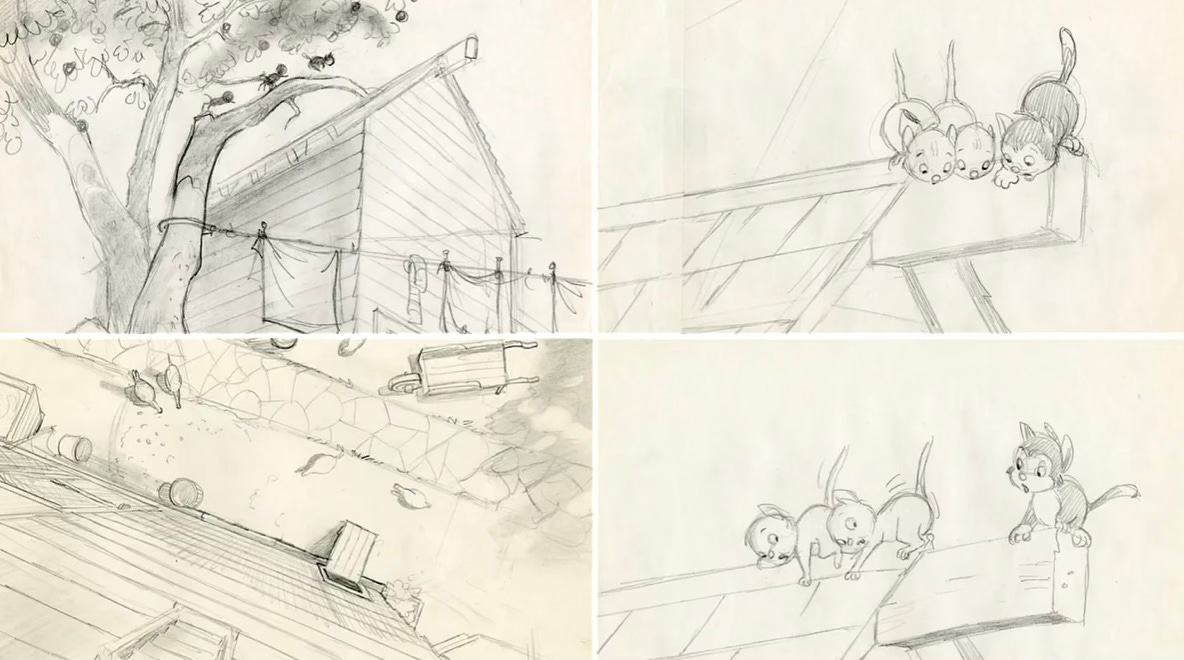

On the Animation Obsessive Substack, I read that in the 1970s, Don Bluth led a group of Disney animators to create their own animation renaissance. Bluth and his colleagues were keenly aware that the knowledge and skills of the original Disney animators needed to be recovered. They had a solution—you've heard of a garage band, well Bluth and his merry gang formed a garage studio.

Here's a section from Animation Obsessive's post about Bluth's animation garage and what inspired it.

'Management said that the Nine Old Men would retire within five or six years. Bluth, Goldman and the rest would soon fill their shoes — with only a rudimentary sketch of what the masters once knew. They needed and wanted to learn faster.

Hoping to bridge the gaps in their knowledge, Bluth started a side project. An independent cartoon made with independent equipment. In his garage.'

'As Bluth remembered, older technical tricks like the "shadows or the reflections or the double passes through the camera" were "evaporating before our very eyes." 1 The problem was bigger than that, too. Bluth and many of the other young trainees didn't know how to make a movie, and they weren't sure how to learn. According to Bluth's colleague Gary Goldman, "We didn't even know what questions to ask."

"We were learning to animate," Goldman explained. "We were learning to in-between, clean up … and we said, 'Wait, there's so much more we need to know.'"

That included writing, scene planning, editing and more. Even the Nine Old Men had "forgotten" much of what went into Disney's older films, said animator John Pomeroy. Speaking to the press in the '70s, Bluth described this unsettling moment:

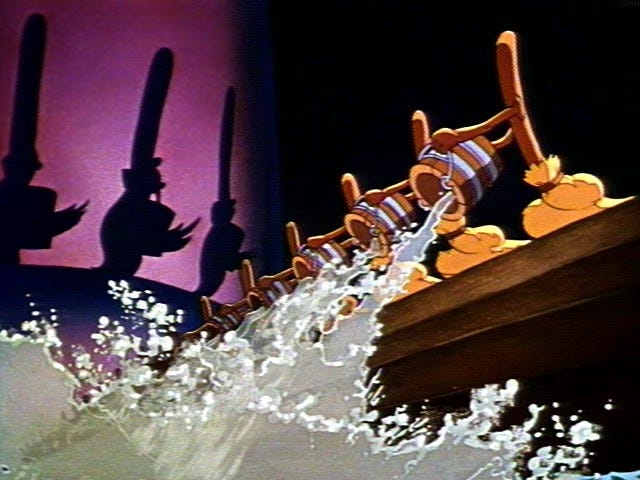

I was watching The Sorcerer's Apprentice part of Fantasia recently and I marveled to Ken Anderson, one of the veterans, about the water. It was so transparent. So wet. I asked Ken how they did it. … The man who created that water is long gone, Ken told me, and no one ever did get around to writing the process down. "Nice, isn't it?" he said. "We've never gotten it that way again." If that happens in too many areas, the whole heritage is gone.2'

Please read the whole Animation Obsessive substack here for the full story of Bluth's animation garage.

As the industry tries to guide the use of AI, like Bluth, we should also consider what efforts are being made to preserve current skills and knowledge. Just like the game we forgot to save on Nintendo, we'll miss it when it's lost.

Thanks very much for the shout-out! You make excellent points about the problem of knowledge disappearing. It's something we encounter all the time in our research -- critical sources of information just vanish into thin air. Many of them can't be replaced, especially when it comes to the online stuff. (One of the first things we do after an issue goes out is make sure that all the sources are properly backed up, either locally or in the Wayback Machine!) There really is this idea that knowledge only increases over time, but it's so easy to lose things. Preservation is essential.

This is a great piece of writing.

Re: the dome in Florence, I very highly recommend reading the book, "Brunelleschi's Dome," by Ross King. https://www.strandbooks.com/product/9781620401934?title=brunelleschis_dome_how_a_renaissance_genius_reinvented_architecture